Specialists at the Maryland Zoo know how important it is for animals living in captivity to be able to socialize, rest, and feed as they would in the wild. But helping bobcats Kilgore and Josie achieve those natural feeding behaviors has posed a challenge.

“These behaviors are incredibly difficult to elicit in zoos for many reasons, but in this case, it’s primarily because the general public doesn’t want to see a bobcat kill a rabbit when they visit the zoo,” explains Joey Golden, the curator of animal behavior at the Maryland Zoo.

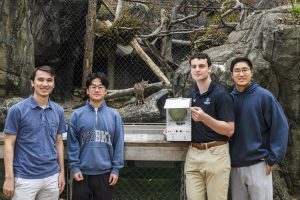

Enter students from the Johns Hopkins Multidisciplinary Engineering Design course. As part of their final project, they were tasked with creating an automated hunting opportunity that allows the zoo’s bobcats to express proper feeding behaviors without ever killing live prey. The team—mechanical engineering students Will Leger and Raphael Stadler and computer science students Jonathan Liu and Peter Xu—will present its work at the Whiting School of Engineering’s annual Design Day on May 1.

Previously, the bobcats “hunted” for their food by solving static puzzles; for instance, the food might be hidden in containers that challenged the animals’ ability to gain access. The Hopkins students wanted to better elicit the cats’ natural seven-step hunting process: identify, stalk, chase, pounce, swipe, kill, and dissect.

Their solution? A high-tech take on the classic “Whac-A-Mole” arcade game.

In this implementation, prey “nodes”—or boxes that might contain food—pop up around the habitat for the bobcats to identify and stalk. When activated, each node plays an audio clip of prey noises; this signals to the bobcats that it’s time to hunt.

Kilgore in the bobcat enclosure at the Maryland Zoo.

“When they interact with a node, they’re sensed with its ultrasonic sensor, which communicates with the other nodes and the main system through radio frequency signals,” says team member Will Leger.

A user interface on a nearby computer allows the zookeepers to vary the number and pattern of nodes that pop up so that there’s a new “game” for the bobcats to play every time.

Once the bobcat is sensed at the last node, a mechanism releases a food-filled “boomer ball” on a slope so that it rolls around the exhibit. The bobcat can then chase it, batting it to release the food.

The students appreciate the unique challenge of designing for animals.

“Because we’re not working with human end users, it’s hard to test as we go along,” says Leger. “Obviously we’re doing it, but the bobcats don’t speak English, so it’s a little hard to get a feel for how much they care.”

The students are designing the system to be used inside of the bobcats’ exhibit so that it’s visible to the public. And since most felines share the same hunting processes, they hope their system can eventually be utilized for larger cats like lions and tigers, too.

“Just with a lot stronger materials!” Leger adds.

See their project in action at this year’s Design Day.