Until recently, 3D surface reconstruction has been a relatively slow, painstaking process involving significant trial and error and manual input. But what if you could take a video of an object or scene with your smartphone and turn it into an accurate, detailed model, the way a master sculptor creates masterpieces from marble or clay? Its creators claim that the aptly-named Neuralangelo does just that through the power of neural networks—and with submillimeter accuracy.

A joint project by researchers in the Whiting School of Engineering‘s Department of Computer Science and tech giant NVIDIA, this high-fidelity neural surface reconstruction algorithm can precisely render the shapes of everyday objects, famous statues, familiar buildings, and entire environments from only a smartphone video or drone footage with no extra input necessary.

The algorithms that power virtual reality environments, autonomous robot navigation, and smart operating rooms all have one fundamental requirement: They need to be able to process and accurately interpret information from the real world to work correctly. This kind of knowledge is achieved through 3D surface reconstruction, in which an algorithm takes multiple 2D images from different viewpoints to render real-life environments in a way that other programs can recognize and manipulate.

The Neuralangelo project was initiated by Zhaoshuo “Max” Li—who earned a master’s degree in computer science from the Whiting School in 2019, followed by a PhD in computer science in 2023—during his internship in the summer of 2022 at NVIDIA, where he is now a research scientist. His goal was not only to enhance existing 3D reconstruction techniques but also to make them accessible to anyone with a smartphone.

“How can we acquire the same understanding as humans of a 3D environment by using cheaply available videos, thereby making this technology accessible to everyone?” he asked.

Working with Johns Hopkins advisors Russell Taylor, John C. Malone Professor of Computer Science, and Mathias Unberath, an assistant professor of computer science, and NVIDIA researchers Thomas Müller and Alex Evans, project manager Ming-Yu Liu, and internship mentor Chen-Hsuan Lin, Li set out to democratize 3D surface reconstruction.

Qualitative comparison of COLMAP, a baseline approach with missing and noisy surfaces, and Neuralangelo.

The team’s first step in the creation of Neuralangelo was addressing the issues that earlier reconstruction algorithms faced when rendering large areas of homogenous colors, repetitive texture patterns, and strong color variations. Because traditional algorithms use analytical gradients that only look at and compare sections of local pixels at a time, they produce inaccurate reconstructions surfaces that are “noisy”—with blobs floating above a roof, for example—or missing, with holes in what should be a solid brick wall, the team says.

“The easy solution is to add manual input,” Li explains. “And you do get better results then, but not at Neuralangelo’s level.”

Instead of increasing human effort, the Neuralangelo team addressed the root of the problem, opting to use numerical gradients in their multi-resolution hash grid representation, which significantly improved the algorithm’s reconstruction quality. This means that Neuralangelo looks beyond local pixels and uses a more holistic approach to sharpen and enhance detailed surfaces and further smooth flat ones, while still capturing all the important details of a scene, the team states.

The researchers also implemented a coarse-to-fine optimization process. Akin to a sculptor carving finer and finer details out of a chunk of marble, the algorithm begins at a coarse hash resolution—picture a crude, rough estimate of an object or scene—and then incrementally increases the resolution to “carve out” finer details and intricacies until it achieves a high-fidelity, realistic 3D reconstruction, the team says.

They then moved on to adapt the algorithm to extract images from manually captured 2D videos. Where traditional algorithms suffer when confronted with video artifacts like exposure variations, such as moving from direct sunlight to heavy shadow, Neuralangelo’s architecture inherently allows it to accommodate such variations, which occur naturally in realistic video capture, Li explains.

The team points to Neuralangelo’s reconstruction of the exterior of Shriver Hall from a two-minute drone video as an example of its capabilities.

From left to right, Neuralangelo’s RGB rendering, 3D mesh surface output, and normal map of Shriver Hall.

No fancy measuring device—like lidar, which often costs hundreds or thousands of dollars—is needed to capture an operating room, a street scene, or a room in your home; you can achieve the same quality of render with just your smartphone camera, Li says.

The quality of the input video still affects the final result, but smartphones, drones, and professional cameras all work, according to Li.

“I tell people, ‘Garbage in, garbage out,'” he says. “But that’s pretty much true for any algorithm input.”

Neuralangelo still struggles with highly reflective surfaces. Due to its high representation power, it tends to fully reconstruct scenes reflected in mirror-like surfaces, rendering something more like a diorama than flat glass, but NVIDIA’s research team says they are already working to resolve this issue. Li also hopes that through publicly available source code, he and the greater computer graphics community can optimize the algorithm to get results within minutes.

In the meantime, Neuralangelo is being lauded as an exciting development for 3D-printing enthusiasts, video game and CGI asset designers, and for use in surgical applications. Li even employed Neuralangelo in his dissertation, using it to produce a high-fidelity reconstruction of a patient’s skull for use during complicated skull base surgery.

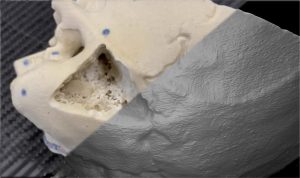

Neuralangelo’s 3D mesh surface render of a skull as compared to the base image.

He envisions future augmented reality applications that alert surgeons to their proximity to a patient’s brain, like self-driving cars’ pedestrian proximity alerts.

“For humans, it’s very hard to quantify specific distances—whether we’re talking meters away or millimeter accuracy—but algorithms can provide such complementary skill sets,” he explains.

The Neuralangelo team presented their findings in late June at the 2023 Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference in Vancouver, Canada, and Li says there is already much excitement for the algorithm’s future.

He likens future virtual assistants using Neuralangelo to Iron Man’s “J.A.R.V.I.S.”—able to interact with users, give real-time feedback, and, most importantly, understand exactly what’s going on in the real world.

“We’re imagining a Neuralangelo that is aware of more than what the geometry of an object looks like; it understands what it’s looking at,” he says.

Li credits the knowledge and skills he acquired and sharpened while completing his doctorate at Hopkins with helping to prepare him to tackle such real-world challenges and connecting him to opportunities in industry.

“The Computer Science Department’s combination of theoretical foundation and hands-on experience prepared me to understand and tackle research challenges,” he says. “The faculty also actively promote industry collaborations and helped connect me with world-leading researchers within JHU and beyond.”

See Neuralangelo in action, courtesy of NVIDIA: