The first time monetary value was assigned to bitcoin—a theoretical, nebulous token exchanged around the Internet—was in 2010 when a Florida programmer traded 10,000 coins in exchange for two Papa John’s pizzas. With that trade, one bitcoin was assigned an initial value of less than a quarter of a penny.

Today, a single bitcoin could purchase 1,500 Papa John’s pizzas, pay for delivery, and provide an extremely generous tip for a driver.

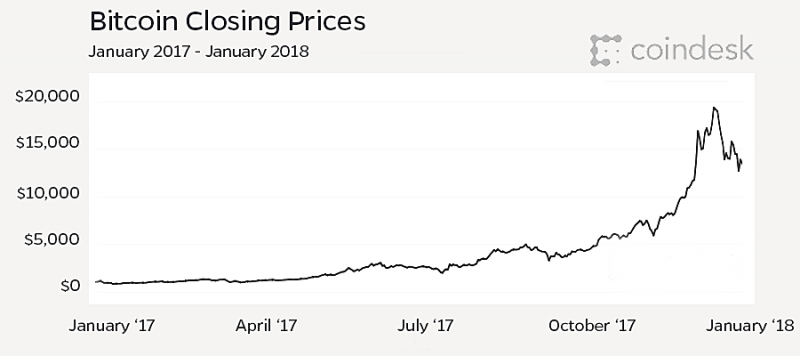

Over the past year, bitcoin has soared in value, withstanding heart-stopping crashes and reaching closing prices as high as $19,000 per coin. The currency’s ability to climb rapidly in value has attracted not only those who use it as a form of digital payment, but also speculators who’ve bought in as investors with the hopes of getting rich quick. (Full disclosure: The author of this article owns .0067 of a bitcoin, and larger fractions of other cryptocurrencies not mentioned here.)

But what is bitcoin and how does it work? And what does the craze tell us about the future of finance?

The concept of cryptocurrency was first described in a 2008 white paper published under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto. Nakamoto’s identity has never been made public, but whoever it is shuttered their online presence in December 2010, disappearing into obscurity with about a million bitcoins—an alleged stash that would now be worth more than $10 billion.

The system Nakamoto described was a way of exchanging currency without the use of a centralized bank or mint, with transactions occurring directly from person to person and protected by advanced computer encryption. Cryptocurrencies are highly secure, in part because varying degrees of anonymity are provided to users, but also because the digital network doesn’t rely on a single server or institution like a bank to control or store records.

Since Nakamoto first introduced bitcoin to the world, several other forms of cryptocurrency—collectively called alt-coins—have also risen in popularity. In 2013, Johns Hopkins cryptographer Matthew Green helped develop a form of cryptocurrency called Zerocoin with a group of graduate students. Their concept has developed into a commercial currency called Zcash, which now has a $1.7 billion market cap.

“The biggest concern is that we’re in the middle of this crazy bubble, and that it’s all going to burst,” Green says. “If it does, people are going to look at the underlying technology and say, ‘Wow this is a disaster, let’s never talk about this again,’ and I’d be really sad about that because I think this is an amazing and promising area.”

Despite the risks, bitcoin’s climbing prices attract investors by the thousands to online “wallets” where coin purchases are made and managed. The leading platform for buying and selling cryptocurrencies, Coinbase, boasts more than 13 million user accounts—more than the number of brokerage accounts managed by banking giant Charles Schwab—with a reported 100,000 new users registering every day during a single week in late November.

Image Credit: Data provided by Coindesk

Most of these investors buy whole or fractions of coins and use these holdings like a stock or a bond, buying low and hoping that coin values increase, later trading them for U.S. dollars. There are a growing number of retailers that accept bitcoin as a form of payment, including Microsoft, Overstock.com, Expedia, Dish Network, the global nonprofit Save the Children, Wikipedia, Tesla, the student bookstore at MIT, and the online retailer Shopify.

The trouble with using bitcoin as a currency and the risk of using it as an investment—especially during this unpredictable bull market—is the extreme fluctuations in exchange rates, and the fact that coin values are not backed by a commodity like gold, the way the U.S. dollar originally was.

“Bitcoin accepted” sign in the window of a coffee bar in downtown Zurich, Switzerland in January 2015.

“Similar to any other asset or security, bitcoin prices are driven by supply and demand,” says Jim Liew, an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School who specializes in big-data machine learning and wealth management. “If there are more buyers than sellers, the price will go up. If there are more sellers than buyers, the price will go down.”

The price of bitcoin can also be subject to manipulation, he says.

“Over the summer, two competing camps were at war over a bitcoin operational decision, and it prompted a volatile response” he says. “The losing camp attempted to punish bitcoin holders by abruptly selling large holdings and causing the price to fall dramatically. But the market recovered and is climbing to greater heights—for now.”

As bitcoin’s value and popularity soar, so too does curiosity about how the currency works.

Bitcoin transactions occur when a coin owner signs part of or all of a coin to another user—similar to endorsing a check over to another person. These transactions are publicly announced on a digital ledger called a blockchain that is passed around the internet.

The bitcoin network doesn’t have a centralized company or fleet of staff members who maintain the blockchain—that’s where bitcoin miners come in. They use highly specialized computer processors to make sure no one has spent the same bitcoin twice. These processors, called ASICs, are highly efficient at working in the encrypted network, so part of the mining process involves solving complex mathematical equations. These equations artificially slow down the mining process and help keep it competitive.

Despite the efficiency of the ASICs, mining still requires a substantial amount of electricity to power the computer processors, and as the network grows, so does the energy required to maintain it. So much electricity is needed, in fact, that the bitcoin network alone reportedly uses as much electricity as 3 million American households.

Miners are reimbursed for their work—and their electricity—with bitcoins that have been freshly minted. So to speak.

Cryptocurrency is attractive as a democratic system of finance, but bitcoin has particular limitations that competing alt-coins have sought to improve. Although the bitcoin blockchain is encrypted, it’s not entirely anonymous, for example. Public keys are used as digital signatures so it’s possible to track transactions—and in some cases determine who is behind a payment.

Green, the Johns Hopkins cryptographer, aimed to address this privacy deficiency when he developed Zerocoin, which allows computers to verify transactions on the blockchain without relying on personally-identifying information.

“Back in 2013, my grad student Ian Miers and I were looking at bitcoin, trying to find ways to make it anonymous,” he says. “Zerocoin allows you to make transactions where nobody knows who is paying whom—even the person you pay doesn’t know who you are.”

This type of enhanced, zero-knowledge blockchain system is starting to attract the institutions cryptocurrencies were originally designed to bypass: big banks.

“Banks want to redo their internal systems in a way that increases anonymity,” Green says. “If you’re a bank, and you’re doing a trade with another bank, you don’t want some third or fourth or fifth bank learning about the details of that trade. But you can’t do that with the [traditional] blockchain. If you want to have a blockchain where lots of banks are participating together, you need to keep your transactions secret. Zero-knowledge means I can do my transactions on the blockchain, but nobody else can see what they are, so I still get confidentiality.”

Carey Business School expert Liew says the evolving technology is also attracting businesses and credit card companies that want to incorporate cryptocurrencies into their payment options in order to draw in bitcoin users—and the collective financial value they represent.

“More traditional companies are announcing that they are accepting cryptocurrencies, so they may gain traction at some point, but it’s still too early to make that call,” he says. “It’s going to be a worthwhile currency given more time, but there will be more heart-wrenching draw-downs along the way.”

Those value draw-downs may scare away skittish investors—and may even damage the finances of less-savvy traders. But they will also likely drive innovations in the blockchain technology, like those developed by Green.

“I think we’re seeing version 1.0 of what cryptocurrency can be,” Green says. “But years from now, nobody will care about version 1.0. They’ll care about version 5.0 or 10.0. But this is going to be really important in the future.”

Adds Liew: “This is the future of finance. Without a doubt.”